Almost 50 years ago on June 29, 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a groundbreaking ruling holding that the death penalty in its current form was cruel and unusual, and hence unconstitutional.

The case came out of Georgia, but the impact of the Court’s ruling was sweeping: it resulted in the abolition of all state and federal laws that allowed the death penalty and overturned the death sentences of over 600 people.

For the first time in the country’s history, the death penalty did not exist — death rows were cleared and no one could be sentenced to death under existing statutes.

While the Court’s ruling made headlines, it was not that surprising as the country emerged from a period of turmoil and change. Protests against the Vietnam War had reached a peak in the early 1970s. The '60s brought about disruptions in society and ended with the tragic assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy. Cities burned, including Washington.

The weight of so much killing became increasingly unbearable. Many believed that the Court’s decision in Furman v. Georgia meant the end of capital punishment in America—and good riddance.

But that was not to be. The Court’s actual 5-4 ruling was just a few paragraphs, but there were nine opinions explaining each justice’s interpretation of what had happened.

The consensus was that the death penalty itself was not held unconstitutional, only the way it was being applied. The death penalty was cruel because it was applied arbitrarily — there were almost no standards as to who would die and who would be spared.

The undercurrent of the debate, which the justices barely addressed, was that this seeming randomness played out in racially discriminatory ways. As Justice William Douglas remarked, the arbitrariness was “pregnant with discrimination.”

Thirty-five states took up the signal from the Court that the death penalty might be allowed to continue under revised laws. States tried many different approaches, and in 1976 the Court ruled on five state statutes, upholding the laws of Georgia, Texas, and Florida, while striking down those from North Carolina and Louisiana.

States (and the federal government) now had a blueprint for bringing back the death penalty.

Forty-five years later, the “new and improved” death penalty ship that launched in the 1970s is perilously leaking and on the verge of permanently sinking.

The scars of so many exonerations from death row, the obvious infection of racism, and even the inability to devise an acceptable method of execution, have led the majority of states to either abolish the death penalty completely or effectively halt its use.

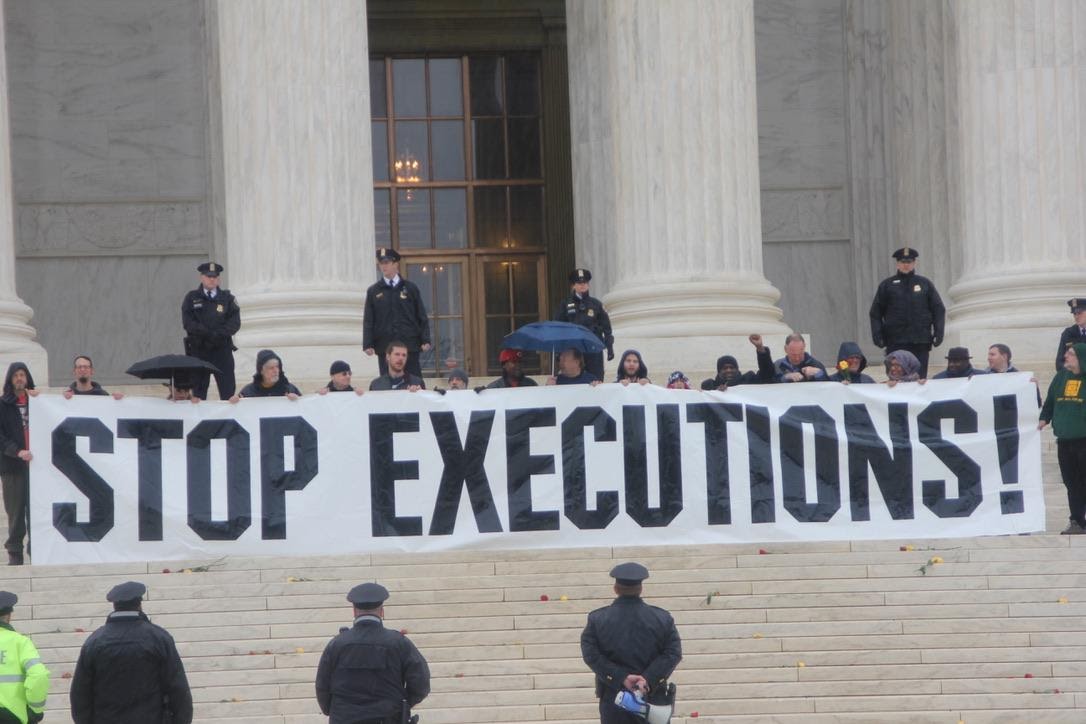

Executions and death sentences have dropped by more than 80% since 2000. Perhaps, once again, there have been too many deaths to bear, too many people treated like objects rather than with the dignity they deserve.

Not surprisingly, there have been efforts to revive capital punishment again. The previous presidential administration tried to use executions as an election strategy, while various states threaten to employ draconian methods of execution — the gas chamber, the electric chair, and firing squad — in an attempt to lift the barriers to their obtaining the lethal (but antiseptic-looking) drugs they prefer to use.

A definitive ruling on the death penalty from the Supreme Court may have temporarily receded from the horizon, but the country is rendering its own opinion: it’s time to end the death penalty for good.