In my early college years in Italy, my criminology professor was assassinated by Red Brigade, an Italian terrorist group. The need for justice became an open wound in me, with an abyss of questions: are forgiveness and change really possible in the face of the most heinous crimes?

The desire for a justice that restores has been at the heart of my human experience ever since, in my work in the United States as a teacher and then as a filmmaker.

When I heard about Brazilian prisons run by volunteers and the incarcerated people, I knew I had to make a film about it.

In January 2019, I went to Brazil and spent a week filming in the men’s and women’s prison facilities of Itaúna and São João del-Rei. It became the most impressive redemption experience of my life.

What I encountered in Brazil was a prison with bars but without guards, without police, without weapons, and also without violence, corruption, drugs, and discrimination. Recuperandos, or recovering persons, as they are called, are the ones securing the prison. They dress in civilian clothes, cook their own meals, work, study, and attend group therapy sessions.

Each recuperando quite literally has in their hands the keys to walk out of the prison, and yet there are virtually no escapes. As one prisoner puts it, “No one escapes from love.”

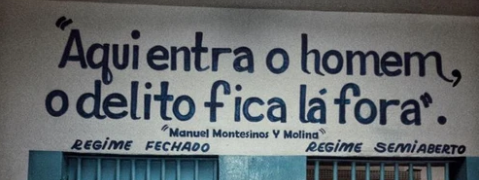

Itaúna and São João del-Rei are facilities run by APAC, or the Association for the Protection and Assistance of the Convicted. APAC began in Brazil in 1972 when Dr. Mário Ottoboni, a lawyer and passionate Catholic, and a handful of volunteers set out to revolutionize the way people administer prisons. They founded their own restorative justice-based system, where incarcerated persons are supported in understanding the consequences of their actions, taking accountability, and unlocking the future. On each APAC entrance door, it says: “The person enters, the crime stays outside.”

Over the course of 50 years, APAC has released nearly 48,000 recuperandos back into society. Incredibly, their recidivism rates average around 15% and monthly incarceration costs are about $250 per person. (By contrast, Brazil’s state-run prisons average at 70% recidivism and $800 incarceration costs.)

There are over 100 APACs in various stages of development in Brazil, and the approach is spread in 12 countries.

12 countries, but not yet the United States, where one out of every 100 people is behind bars, where recidivism rates hover between 60 and 70%, and where prison conditions can be so inhumane that even low-risk offenders are released as broken and hardened versions of their former selves.

That’s why it was so meaningful to me that, when my documentary, Unguarded, was finally released in 2021, it premiered in a Louisiana prison. The day after the premiere, a warden from the Lafourche County Sheriff's Office wrote to me: "For me it was rejuvenating. Stories such as this one refuel my desire to see something different for the men and women who are incarcerated”.

APAC is neither a perfect system nor a recovery factory that seeks to save people in a mechanical way. Besides, as Valdeci Ferreira, director of The International Center for the Study of the APAC Method (CIEMA), puts it, the world we envision as idealists and as Christians is a world without prisons. But “for as long as this utopia does not come about, let us at least treat people with respect and dignity.”

APAC not only opens a viable alternative to inhumane incarceration. It is also a radical appeal to people’s freedom to choose life and restoration. An appeal to recuperandos, but also to all of us.

What I saw in Brazil is the humanly impossible come to fruition. It shook me to my core, and reopened the old wound caused by my professor’s murder. But there was something new: I knew forgiveness and change are really possible. For others, and for me. I have seen it firsthand.